"But how does the mountain caretaker receive the message that the volcano will soon erupt?"

"Spiritually."

"... wouldn't seismometers be preferable?"

The bad ass Indonesian cycle team

I was standing on the rough gravel road that led up the side of Indonesia's most active volcano, beating the nation's rather staggering number of 127 active cones to that title. The last major eruption had been in 2010 and the skeletal remains of two cows that had been caught in the burning ash clouds stood just behind me. Since previous eruptions had occurred in 2006 and 2004, I felt my query regarding mountain monitoring were well made, although arguably should have been posed before embarking on a trip entitled "Jeep Lava Tour".

But... YOLO.

Mount Merapi translates literally to "Mountain of Fire" in Indonesian, making the true name "Mount Mountain of Fire" or "OMG IT'S A VOLCANO RUN". It is situated just outside Yogyakarta in central Java. The roads up the mountain are too rough for almost anything other than a jeep or motorbike, with the exception of the Indonesian cycle team we passed training on a the dry riverbed that had been etched out by passing lava. I made a mental note never to bet on a race against those guys.

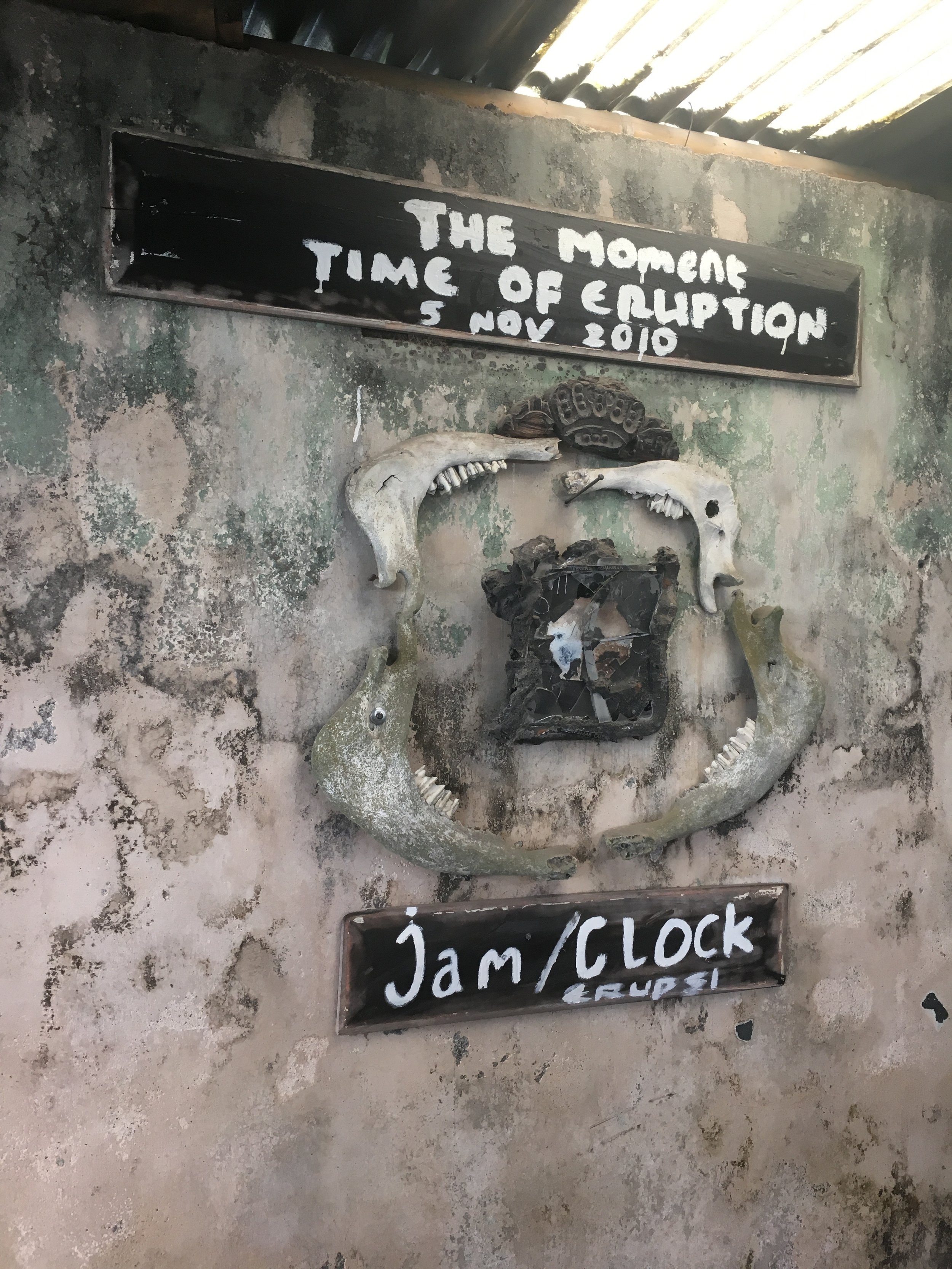

The jeep tour lasts a few hours and one of the first stops is at a house that was swamped by the ash clouds in the 2010 eruption. Most of the villagers in the area were evacuated, but the family that owned this property collected together artefacts that had been left behind. As well as the bones of cattle, there is a clock that had stopped at the time of the eruption and bikes, chairs, televisions, pots and pans that had distorted and buckled in the intense heat.

Interestingly, we passed other settlements close to the burnt out shell of this museum that appeared unaffected. When quizzed, our jeep driver suggested the hot ash had a path determined by wind direction and properties either side of the clouds were safe. I remain skeptical there would be such a sharp edge to the destruction, but the architecture does imply something of that ilk.

The grave of Mbah Maridjan, caretaker of Mt Merapi.

While scientific methods are employed to monitor Merapi, the mountain does have a spiritual caretaker who makes offerings to the volcano's lava-filled maw to pacify whatever nature deity controls such destructive powers. The current caretaker inherited his role from his father who died in the 2010 eruption after refusing to evacuate. According to our jeep driver, the 83 year old was ordered off the mountain by the Yogyakarta Sultan himself but declined to leave his post because it was the Sultan's father who had ordered him to take that position.

The obvious problem being that the current sultan wouldn't be sultan if his father was still alive.

Allegedly, the caretaker claimed that he would know if his leige wished him to abandon his post. Since his body was found bowed in prayer and caked with soot, presumably no permission was granted. I wondered vaguely whether it was possible to still be sent to hell even if you died quite some time ago.

Batu Alien: the "face" is angled about 45 degrees to the top right.

The grave of the caretaker is now a revered site on the mountain, with the grave marker taking a prominent, flower covered, place in the little cemetery. I have two conflicting thoughts about this and both are guessable.

Further up the mountainside is the site of the "Batu Alien"; a stone supposedly shaped like an alien's face that was hurled out of the volcano during an eruption. The view was pretty and that's all I'm saying on that subject.

The highest point on the tour was a location known as Kaliadem on Merapi's south side and 1100m above sea level. Nothing much now exists here except for a bunker that was created to protect people in case of landslides. Two people died here during the 2006 eruption, as the bunker could not protect them from the extreme heat rolling over their heads nor the mud slide that barraged through the thick doors and filled the small space. While you can now enter the bunker once again, a central pile of mud has been left as a memory of what occurred.

As an aside, our jeep has the coolest sticker.

Bunker entrance at Kaliadem.

After escaping the potential ash-covered demise of the jeep tour, we visited the Ullen Sentalu Museum. The building for this private museum is worth the visit alone, being tucked within a shady forest and constructed from stone that radiates coolness like the inside of a cathedral. The exhibits are in individual rooms connected through the outside by decorated stone walkways. Visitors are taken around by tour guides and almost no photographs are allowed.

The museum is owned by the Haryono family who made their fortune in industry but clearly have strong ties with the Indonesian royalty, since many of the exhibits involve portraits or items belonging to the different members.

Royalty itself is a complex subject in a conglomerate nation which only combined to gain independence from colonial rule in 1945. However, the only royal with current political power is the Sultan of Yogyakarta who is governor of the city. This unelected role stays with the sultanate due to the assistance of Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX in overthrowing the Dutch.

The outside of the Ullen Sentalu Museum

The Yogyakarta royal branch was created in one half of a fracture in 1745, which split the Javanese sultanate into the Yogyakarta Sultante and the Surakarta Sunanate. It was from these two sides that the treasures in the museum originate.

Portraits of the Indonesian royal family show a number of reoccurring themes. Clothing is usually made of the traditional batik dyed cloth, with a design of dragons only worn by kings. The mother of the current monarch is not depicted wearing a crown, but carrying keys. Such lock openers were symbols of power since they allowed access to boxes containing the family's considerable wealth. While the royal family are now muslims, none don the traditional hajib. Our guide told us there was no law regarding this but a personal choice to follow the traditional royal dress style, which predates Islam in Indonesia.

One room in the museum is dedicated to Princess Tinneke, who is described as the "broken hearted princess" as she was forbidden to marry the man she loved by her mother. The room is decorated with letters sent to Tinneke by family and friends from around the world to offer words of comfort. A quick scan of these missives suggests support was in rather short supply, since quite a few seem to be telling her to just deal with her boy issues. Deal she did not, however, and waited until her brother took the throne and granted her permission to marry the man she loved. Her mother refused to be united with her stubborn daughter for twenty years.

The "broken" image of Java culture

Another princess of a similarly strong mindset was Gusti Nurul, who flat out rejected the polygamy common of that time, and refused to marry any suitor who already had a wife. In an entertaining contrast to Tinneke, Gusti Nurul became the princess to cause broken hearts, as she rejected multiple marriage proposals from prominent (but married) men. She eventually married a solider who --along with civil servants-- were forbidden from taking multiple wives for reasons unknown.

Despite a history of strong women, the sultanate can only be passed down through the male line. This has left the current sultan with a dilemma, since he has five daughters and no sons. His personal vote has been to break with tradition and see his eldest daughter inherit his title, but it is a proposal that has met strong opposition, not least from his brothers.

The museum ends with a stone mural depicting Javanese traditions. It is mounted at an angle to symbolise that young Indonesians are rejecting their heritage and ignoring their culture. As we stepped outside the museum, we were flanked by some highly goulish statues with no explanation at all. If the mural was for broken youth, these scream-like visages might be the warning for the future.